Denna uppsats skrev jag i början av min Masterutbildning vid Voice Study Centre (UK) och University of Wales Trinity Saint David. För er som är på väg att skriva en avhandling eller är intresserade av vokalpedagogisk forskning, kan den bidra med kunskap och inspiration, samt reda ut vissa viktiga begrepp. / Anna Elisa Lindqvist, lärare på StOC.

Critically evaluate a selected range of methodological approaches appropriate for research in work-based settings, with due consideration to research ethics and insider research issues.

Since the 1980’s, much of the discussion about social science has revolved around the distinction between qualitative and quantitative research (Morgan, 2007). I recognize this from my undergraduate research courses, where this polarity was the main (if not only) focus. This course has made me aware of the pre-ordinate role of paradigm, how paradigm, in turn, is linked to ontology and epistemology, and the importance for researchers to align their methodologies with their paradigms as well as their ontological and epistemological beliefs (Guba & Lincoln, 1994; Mackenzie & Knipe, 2006). I find the beginning of Cohen et al.’s Research Methods particularly clarifying: “This view moves us beyond regarding research methods as simply a technical exercise and as concerned with understanding the world; this is informed by how we view our world(s), what we take understanding to be, and what we see as the purposes of understanding” (Cohen, et al., 2011).

Ontology and Epistemology

Ontology reflects how we view reality. Do we consider reality as objective, external to ourselves? Or do we see it as a product of individual interpretation, where we are co-constructors of our reality? Our ontological beliefs have consequences for our epistemological positions – i.e. how (or whether) we gain or create understanding. If we believe that there is one, objective Truth waiting to be discovered, then the epistemological position would be to stand beside that reality, studying it as detached observers. If, on the other hand, we believe that there is not one single truth, but that reality – being filtered through our personal backgrounds, values and prejudgments – manifests itself in multiple truths, then we cannot be objective observers, but co-creators of “reality” (Cohen, et al., 2011).

As a classical voice teacher, I would view some physiological factors and how they result in certain acoustic phenomena as “single truths”. However, when it comes to coordinating muscles, and definitely when entering the field of pedagogy, there is a myriad of “realities” all entangled in the complexity of human behavior and social dynamics – This is where voice science develops into voice pedagogy.

Paradigms

How researchers align themselves to ontology and epistemology defines their paradigm. Morgan has examined various definitions of this term and concluded that the most common definition among social scientists is “shared belief systems that influence the kinds of knowledge researchers seek and how they interpret the evidence they collect” (Morgan, 2007, p. 50).

If our ontological worldview is that reality is external to us and our role as researchers is the objective observer, we align ourselves with the positivistic paradigm (Cohen, et al., 2011; Guba & Lincoln, 1994). For long, this was the only paradigm of science, as the scientist’s mission was largely to study natural phenomena so as to classify, control and predict nature. This is still the task in physics and mathematics, and positivism is sometimes referred to as “the scientific method” (Mackenzie & Knipe, 2006). The main methodology for the positivistic paradigm is the quantitative approach, which purpose is to investigate the measurable, by studying a quite narrow topic, and presenting the results with numerical and statistical analysis (Mertler, 2016).

In the beginning of social science, the positivistic stance was inherited from physical science, together with the epistemological belief that logical deductions (regarded as “facts”) from natural science could be extended to human behavior and directly applied on the social world (Bracken, 2010; Mackenzie & Knipe, 2006). Such approach requires that the world exists independently of our perceptions of it, and that human behavior “is manifest of an ordered and rule governed external reality” (Bracken, 2010, p. 2) – hence not under the control of free will. It presupposes that “the world of social interactions (…) is a rational, external entity and responsive to scientific and positivist modes of inquiry” (Bracken, 2010, p. 2). This approach has obvious limitations when it comes to exploring the complexity of human interactions, which led to the development – in the mid-20th century – of both post-positivism and constructivism (also called interpretivism), which opposed the idea of human behavior as rule-governed and the possibility for the researcher to be a detached observer (Cohen, et al., 2011). Post-positivism opened for the possibility that theories might change over time as new understandings expand our knowledge (Bracken, 2010). Constructivism took everything a step further, by completely opposing the positivistic paradigm, offering an alternative to meet the needs for contextualized understandings of social dynamics (Bracken, 2010; Guba & Lincoln, 1994). The ontological belief is that there is not only one reality, independent from the observer, but multiple realities all filtered through our human experiences. Its epistemology hence considers it impossible for the researcher to be a mere observant, and instead emphasizes that reality is socially constructed (hence constructivism) and always interpreted through individual and cultural filters (hence interpretivism). The methodology most associated with the constructivist paradigm is qualitative research, which aims at uncovering deeper meanings of human experiences (Merriam, 2016).

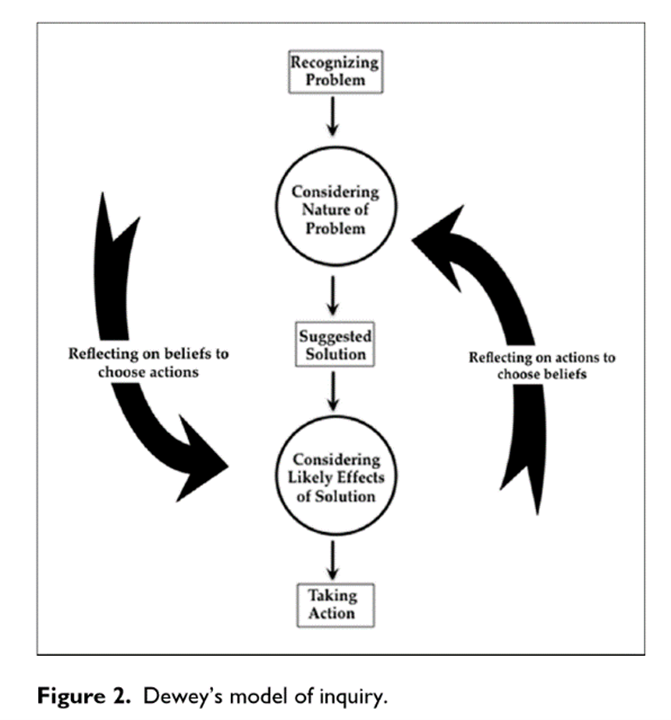

The polarity between positivism and constructivism led to the so called “paradigm wars” (Feilzer, 2010), which was also a “war” between quantitative (by some researchers seen as the only true scientific methodology) and qualitative (by some considered far too subjective) methodologies. Feilzer describe these debates as “long-lasting, circular and remarkably unproductive” (Feilzer, 2010, p. 1), as often happens when a debate gets stuck in polarity. To switch focus from the “either/or”-rhetoric, the pragmatic paradigm developed, which cared less for philosophical definitions and instead placed the research question at the centre of attention, allowing all methodology and methods that could help answering that question, without restrictions of loyalty to either philosophical belief system (Mackenzie & Knipe, 2006; Morgan, 2007). One of the promotors of pragmatism was Dewey, who considered both positivism and constructivism equally valid, being “two sides of the same coin” (Morgan, 2014, p. 1048), as our experiences are constrained by the nature of the world at the same time as our understanding depends upon our interpretation of those experiences.

He advocated “a process-based approach to knowledge” (Morgan, 2014, p. 1048) in which knowledge consists of warranted assertations that are the result of “taking action and experiencing the outcome” (Morgan, 2014, p. 1049). In Dewes model of inquiry, there is a constant and cyclical reflection on both actions and beliefs, where the beliefs influence new actions, and the actions influence new beliefs. Mixing quantitative and qualitative methods – mixed methods studies – had been applied before, and much of the so-called paradigm war revolved around the question if these methodologies were compatible, or mutually exclusive within the same study. Pragmatism was partly a response to the demand for “an underlying philosophical framework for mixed-methods research” (Mackenzie & Knipe, 2006, p. 4).

As my ontological and epistemological views depend on the aspect being studied, I see the pragmatic paradigm as the only possible paradigm for my future research, which may include quantitative, as well as qualitative and mixed methods research. It offers me the freedom to place the research question in focus and apply every methodology suitable for answering that question, which is crucial when inquiring the transdisciplinary aspects of vocal science and pedagogy.

Methodologies

The terms quantitative and qualitative are umbrella terms that contain several methodologies (in quantitative contexts more frequently defined as research designs) appropriate for different kinds of research purposes (Merriam, 2016).

Quantitative designs investigate the measurable, describe and compare variables and present the results with numbers and statistics. They are deductive as they often begin with a hypothesis that is tested with different methods, and conclusive, in that it aims to either verify or disclaim the advanced hypothesis through data analysis. As opposed to qualitative methodologies, the quantitative approach is not as philosophically driven and does not offer as great a variety of methodological choices. It can be either experimental or non-experimental, and can consist of experiments, observations and surveys (Creswell, 2003; Mertler, 2016). Conducting a quantitative research does not make the researcher a positivist, but in that specific research context, the researcher must take the role of the objective observer who merely describes and compares what he or she sees, possibly ending up in predictions or conclusions, and always without subjective reasonings, which instead can be appropriate in a following qualitative study, or in a mixed method research, for which the quantitative study may serve as starting point for further problematizations and explorations.

While quantitative research is strongly reductionistic, by detaching the part to be studied from the whole, isolating it from its context, qualitative research aims at uncovering meaning in context (Merriam, 2016) and is therefore the methodology most associated with constructivism. Qualitative research is not focused on how often or how many, but on which meaning certain experiences have for the persons involved, and how they interpret them (Merriam, 2016). Its purpose is not to present findings that can be representative for whole groups or populations, but to go more in-depth of a phenomenon and explore its dynamic aspects. Qualitative methodologies are to their nature mostly inductive and exploratory in that they do not begin with a hypothesis to be tested, but with broader research questions to be explored. It is discovery-oriented, although a theory may emerge during the process of “observations and intuitive understandings gleaned from being in the field” (Merriam, 2016, p. 34), and therefore, some qualitative methodologies, like grounded theory, are also defined as emergent research. Qualitative research is appropriate for exploring dynamic processes, perceptions and social interactions, and therefore suitable for social and educational science, which are “applied social sciences (…) because practitioners in these fields deal with the everyday concerns of people’s lives” (Merriam, 2016, p. 19). The qualitative approach does not rely on technical or digital methods, but requires the sensitive human analyse to uncover underlying and context-bound meanings (Merriam, 2016).

There are many methodological choices within qualitative research, and I agree with Merriam et al., in that “a challenge especially to those new to qualitative research is trying to figure out what ‘kind’ of qualitative research study they are doing and what their ‘theoretical framework is.” (Merriam, 2016, p. 39). I will explore three methodologies suitable for my future research: Phenomenology, Hermeneutics and Case Study.

Phenomenology and Hermeneutics

Phenomenology and hermeneutics are often used interchangeably and sometimes combined as phenomenological hermeneutics (Dowling, 2004), but there are some core differences. Phenomenology was developed as a ground-breaking new approach to research by Husserl in the first half of the twentieth century, is sometimes considered an alternative to positivism and is strongly related to the development of constructivism (Denscombe, 2014). Husserl opposed the positivistic approaches used in psychology, as they left out human feelings, dynamics and complexity. He, being a mathematic himself, saw the absurdity in applying the same rules on social science as on mathematics (Kakkori, 2009) and aimed at switching focus to experience and interpretation – something that has inspired all qualitative methodologies ever since. Even if phenomenology is a separate methodology (Merriam, 2016; Denscombe, 2014; Dowling, 2004), as a philosophy, it has partly become an umbrella term for methodologies which focus is not measurement or statistical analysis, but more in-depth descriptions of peoples’ lived experiences, perceptions and feelings.

The core (essence) of phenomenology is exploring human experience – especially how people actively (since they are not rule-governed as the positivistic paradigm was inclined to believe) interpret and make sense of those experiences. The basic assumption is that every experience shared by humans (e.g. fear, social exclusion or joy) has a common core, which is its essence – the phenomenon as it is – and that this essence can be understood by studying peoples experiences of it (Denscombe, 2003). Denscombe writes that “the phenomenologist’s task, in the first instance, is not to interpret the experiences of those concerned, not to analyse them or repackage them in some form. The task is to present the experiences in a way that is faithful to the original” (Denscombe, 2014, p. 96). Doing this requires a certain amount of objectivity and ability to put one’s own beliefs aside. Husserl applied what he called bracketing, which can be described as detaching oneself from pre-believes and values, to see the essence clearly (Creswell, 2003; Merriam, 2016). There must therefore be an awareness about one’s own personal beliefs and an effort to minimize them during the research process, and this is a common ethical challenge in all qualitative research. Schütz, who later developed the North American phenomenology, calls this process adopting the stance of the stranger (Denscombe, 2014). However, there has been criticism of the concept of bracketing. Merriam’s description of it is beautiful and quite spiritual: “When belief is temporarily suspended, consciousness itself becomes heightened and can be examined in the same way that an object of consciousness can be examined” (Merriam, 2016, p. 42), but, as she soon points out, “the extent to which any person can bracket his or her biases and assumptions is open to debate” (Merriam, 2016, p. 42).

Even if phenomenology “was seen as a movement away from the Cartesian dualism of reality being something ‘out there’ or completely separate from the individual” (Laverty, 2003, p. 3) and Husserl saw phenomenology as “a way of reaching true meaning though penetrating deeper and deeper into reality” (Laverty, 2003, p. 3), the act of bracketing suggests that there is an external world or truth, that can be observed by a (temporarily) neutral researcher. Phenomenology developed in North America under the influence of Schütz, to concerning itself with pure experiences, but the focus of the European, Husserlian phenomenology is uncovering the essence behind those experiences. Even though this is done through the seemingly constructivist and qualitative in-depth study of human perception and interpretation (Denscombe, 2014), the study of human experiences is mainly the tool which enables the uncovering of the essence, which is the final goal. Therefore, I consider phenomenology still partly clinging to the positivistic paradigm which it wanted to rebel against.

Husserl’s pupil Heidegger took one step further, developing hermeneutics. In contrast to Husserl, Heidegger believed that the focus should be on understanding instead of describing, and also that there is no possibility of bracketing, as all is context-bound and the researcher always influenced by his or her pre-beliefs (Dowling, 2004). Instead of studying the essence, he switched focus to studying the process of interpretation of the essence, hence completely leaving the positivistic approach, rooting himself in the constructivist paradigm (Kakkori, 2009). So, while phenomenology can be defined as the study of essence, hermeneutics can be defined as the study of interpretation of the essence (Paterson, 2005). It is said that hermeneutics focuses on the written word, and it is true that it developed in the 17th century in the process of understanding biblical texts (Heidegger was a theologist), but it then evolved to including other texts, the spoken word and finally into a science of understanding lived experiences (Paterson, 2005; Laverty, 2003). In hermeneutics, there is a constant movement and dialogue between the parts and the whole – something Heidegger developed and illustrated with the hermeneutic circle, which is a cyclical process of understanding, since the parts define the whole and the whole contextualizes the parts (Paterson, 2005).

Gadamer somewhat returned to the importance of language, and developed the Heideggerian hermeneutics further (Dowling, 2004). The two central pillars in Gadamer’s hermeneutics are prejudgement (one’s pre-beliefs, or horizons of meaning, which also according to Gadamer shouldn’t and can’t be set aside), and universality (the connection between a person who expresses him/herself and a person who understands) – both intrinsically related to human language, through which we understand the world (Dowling, 2004). The act of sharing those experiences is what Gadamer defines fusion of horizons, “whereby different interpretations of the phenomenon under investigation (…) are brought together through dialogue to produce shared understanding” (Paterson, 2005, p. 343). This dialogue need not be between persons, but can occur between the researcher and the texts of interest, through the so called hermeneutic conversation – which Gadamer equated with the logic of question and answer (Paterson, 2005). I find Gadamer’s development of hermeneutics particularly interesting and useful for educational research, as it focuses on dialogue and understanding, and as no understanding is considered “better”, but only different.

Case Study

The case study focuses on one, or a few, naturally occurring phenomena, by studying every aspect of it, to understand how all parts are linked together and interact (Denscombe, 2014; Cohen, et al., 2011). An educational case study could include a particular student, a class or a school. Through in-depth studies and narratives, the case study can offer levels of understanding that are not possible with abstract theories (Cohen, et al., 2011), and insights from an individual case that can be applied on a wider scale – “illuminating the general by looking at the particular” (Denscombe, 2014, p. 54) . It can therefore be convenient for small-scale research projects (Denscombe, 2014) and also for work-based research, as it does not require randomization, but encourages deliberately chosen phenomena to study. A case study can be quite flexible in that it may have more than one purpose and also use a wide range of both quantitative and qualitative methods – it is pragmatically rooted in that it is the unique context of each inquiry that dictates the specific methods, as long as the field of inquiry can be isolated from its context in order to be studied (Denscombe, 2014; Cohen, et al., 2011).

The case study is mostly inductive, but can occasionally also be deductive in testing a theory, or even carrying out an experiment. It may not generate enough validity to verify any hypothesis, but it can test how a theory works in practice and thus reinforce or weaken that theory, based on how it works in a specific context. In this way, it can contribute to developing and refining theories (Denscombe, 2014).

The deductive, theory-led case study might be interesting for me, testing theories about how we create certain acoustic phenomena by making physiological changes in the vocal tract and how these changes interact with breath control, and also testing some pedagogic methods to motivate students to do these changes. Within the case study I could use a phenomenological or hermeneutical approach when studying my students’ emotions, motivation and perception. I could apply these methodologies when examining the often-strong resistance many students have towards singing with an open pharynx, as they feel that they lose their “core” and sometimes identity, and also consider the sound “ugly” to them. In a purely phenomenological research study, I would focus on uncovering the essence of that resistance, through the study of my students’ experiences, and describe it as detailed as possible. Applying a more hermeneutic methodology, I would delve even deeper into the experiences of my students, by uncovering all aspects of their perceptions and emotions and study how they interpret those experiences. All this could add value in motivating teachers to persist in this part of teaching classical singing, when they meet resistance from the students. Quantitative studies that show why an open throat is preferable (e.g. by observing correlations with acoustic phenomena necessary for projecting over an orchestra), could add validity in a mixed-methods design.

Methods

Once having chosen what methodology or research design to apply, the researcher will choose what methods best serve the purpose of the inquiry. The methods I have chosen to explore further are observation, questionnaire and interview.

The non-experimental quantitative research designs are measure variables as they occur naturally, by observing them without interfering with them (Mertler, 2016), which makes them more suited for field investigations outside the laboratory. Non-experimental methods can be descriptive, correlational or causal-comparative, and are all part of observations. The descriptive method simply describes one variable, while the correlational method explores the relations between two or more variables – still without interfering with them, which is what makes it non-experimental (Mertler, 2016). Correlational research can describe related factors (explanatory correlational research) and sometimes predict the behaviour of one variable based on another co-related variable (predictive correlational research), but not establish causal relations (Mertler, 2016). The question correlational research can answer is “Does x and y co-relate?” – not why they correlate or which one of them causes the other, even if correlational research can “sometimes obtain strong suspicions that one variable may be ‘causing’ the other” (Mertler, 2016, p. 119). When experimental research is not possible or advisable, researchers can use a causal-comparative approach, sometimes also defined as quasi-experimental research, which may be seen as “bridging the gap” (Cohen, et al., 2011, p. 266) between descriptive/correlational and experimental research. It is included in the so-called ex post facto research, which refers to retrospective studies that investigate possible causal co-relations by observing phenomena that have already occurred (Cohen, et al., 2011). This method can be used when it is not possible to assign subjects to groups randomly, which is required for true experimental research (Cohen, et al., 2011; Mertler, 2016) and also “where it is unethical to control or manipulate the dependent variable” (Cohen, et al., 2011, p. 264).

I could use quantitative descriptive observations for observing – with MRI-technology – how many times my students unintentionally open the VP (velum port), and I could use correlational observations to examine possible correlations between these VP-openings and unintentional narrowing of the mid-pharynx right before the VP-openings. If I were to discover such a correlation, that might lead to a suspicion that unintended nasality might be a symptom of unintentional narrowing of the pharynx.

Observations can be used in both quantitative (systematic or structured observation) and qualitative (participant observation) research (Denscombe, 2014). Systematic observation revolves around measuring the frequency and duration of events, presenting the results in numerical and statistical ways, while the purpose of participant observation is to study behaviors and describing them with words. The systematic observer aims at becoming “invisible”, e.g. by not interacting with the participants at all, while the participant observer – as the name indicates – participates in the setting of inquiry and takes the emic, insider’s perspective (Denscombe, 2014). There are different degrees of participation – with total participation as an extreme where the informants do not know the role of the researcher (Denscombe, 2014). Transparency is of course more ethical as it enables the participants’ consent.

A common method in quantitative research is the questionnaire, which purpose is to provide statistics of “trends, attitudes, or opinions of a population by studying a sample of that population” (Creswell, 2003, p. 201). In a quantitative study, the results should be of the kind that can be presented with statistical and numerical analysis. Therefore, the questions should be close-ended, with dichotomous questions, multiple choice answers, rank offering or rating scales (Cohen, et al., 2011). A questionnaire may also present qualitative aspects, with open-ended questions that allow the respondent to share his or her experiences more freely (Creswell, 2003).

Interviews – like questionnaires – collect data of what people tell the researcher, but primarily belong to qualitative research, as they enable a more in-depth study of the complexity of opinions, emotions, perceptions and experiences. The structured interview is like an oral form of a questionnaire in which both the questions and their internal order are the same for all interviewees, without allowing follow-up questions (Merriam, 2016; Denscombe, 2014). Semi-structured interviews still have a list of questions common for every interviewee, but are flexible with the order and with letting the respondent speak more freely. The questions are open-ended and “there is more emphasis on the interviewee elaborating points of interest” (Denscombe, 2014, p. 186). This emphasis is enforced even more in the unstructured interviews where the respondents are invited to share experiences and opinions in a more conversation-like encounter. It can be “used when a researcher does not know enough about a phenomenon to ask relevant questions” (Merriam, 2016) and the purpose could be to gather enough information to be able to conduct more structured interviews as a next step (Merriam, 2016).

For my purposes, semi-structured interviews might be the most appropriate option, possibly as a follow-up to a questionnaire, as they would allow me “to access participants’ perspectives and understandings about the world” (Merriam, 2016, p. 119), but still keep focus on the questions I want to explore. I will use the one-to-one interview, mainly because I don’t want the interviewees’ narratives to influence one another – a risk also with focus groups, where a small group is gathered and introduced to a theme that they can speak quite freely about (Denscombe, 2014). As Denscombe highlights, one advantage of any kind of observation is that they are first-hand information, while interviews and questionnaires are based on what the respondents tell the researcher (Denscombe, 2014). Another advantage is that the data collecting occurs in natural settings, which makes observations a useful method for insider research (Denscombe, 2014). On the other hand, we need firsthand information from the participants to explore how they feel, think and interpret their experiences (Merriam, 2016). Observations and interviews could complete each other in my research, as I could use interviews to go deeper in to understanding behaviors documented during my observations.

Ethics

Research involves collecting information from and about people. Therefore, the researcher has a responsibility “to anticipate ethical issues that may arise during their studies” (Creswell, 2003, p. 132) and also address those issues as they arise during all parts of the research process (Merriam, 2016; Creswell, 2003). Ethics involves codes for causing no harm for the participants, as well as for research accurateness and objectivity. Qualitative research, being more subjective and participatory than quantitative research, offers ethical challenges – especially when the researcher takes the insider’s perspective, with the dual role of observer and participant (Merriam, 2016). For these reasons, there are continuous debates about the validity of qualitative research, quantitative advocates who still consider qualitative research as being non-scientific. In this respect, Merriam writes that “to a large extent, the validity and reliability of a study depend upon the ethics of the investigator” (Merriam, 2016, p. 266). One of the main questions is how to handle sensitive data that might emerge during data collection, balancing the participants’ privacy against research benefits, and another main question revolves around our own biases, that might influence both the collection and analysis of data (Merriam, 2016). The researcher must be very clear and reflective about his or her own background, position, values and possible biases in relation to the participants as well as the subject studied, and also about his or her relationships to the participants, who are often students, colleagues and sometimes even supervisors, which may cause loyalty conflicts.

There are four key principles of research ethics that stem from the Nuremberg Code and Declaration of Helsinki (Denscombe, 2003). Denscombe writes that “social researchers are expected to conduct their investigations in a way that:

- protects the interests of the participants;

- ensures that participation is voluntary and based on informed consent;

- avoids deception and operates with scientific integrity;

- complies with the laws of the land” (Denscombe, 2003, p. 309)

These codes can be summarized in the call not to cause harm (Merriam, 2016), and that the participants “should not suffer as a consequence of their involvement (…) nor should there be longer-term repercussions stemming from their involvement that in any sense harm the participants” (Denscombe, 2003, p. 310).

It is important to be transparent to the participants about the purpose of the study and to offer complete voluntariness (Creswell, 2003; Denscombe, 2014). When collecting data, there are ethical aspects to be aware of. Both interviews and observations involve collecting data that is sometimes very personal. Observations may present ethical dilemmas when the participants are not in a public, but private setting as the often very intimate setting of singing lessons (Merriam, 2016). The goal for the observer is to melt into the situation in order to observe a natural process, just as it would occur without the observing eye. However – while the researcher has to take into consideration that behaviours often change when someone is observing, as Merriam points out, there are also risks with the informants growing so accustomed to the presence of the researcher, that they might reveal things they would later regret (Merriam, 2016), something that can also happen during interviews. If this occurs, it is the researcher’s responsibility to protect the participants’ privacy (Creswell, 2003). During interviews, it is important to be as neutral as possible, keeping one’s own values and opinions aside, so as not to influence the interviewees. The less structured the interview, the higher the demands on scientific integrity (Merriam, 2016). Similar ethical dilemmas might arise during the process of analysing and presenting the data, as qualitative data is inevitably filtered through the researcher’s own background and belief system (Merriam, 2016). Results must be analysed and reported as they are – not by removing details that might not fit into what the researcher wants to communicate (Creswell, 2003).

Conclusion

Going beyond methodologies, discovering the philosophical roots and paradigms behind them, as well as learning more about methods and the ethical dilemmas I will have to address, has given me valuable knowledge and tools for conducting my future research with more scientific integrity then before. I see vocal pedagogy in Sweden as mostly stuck in either positivism (e.g. Sundberg) or complete subjectivism, and I am motivated to contribute bridging this gap. Learning more about the pragmatic paradigm and mixed-method research has offered me a philosophical framework and structure for mixing quantitative and qualitative methodologies, to develop pedagogic tools that take into consideration the complexity of pedagogic processes at the same time as being rooted in voice science.

Bracken, S., 2010. Discussing the Importance of Ontology and Emistemology Awareness in Practitioner Research. Worchester Journal of learning and Teaching, Volume 4.

Cohen, L., Manion, L. & Morrison, K., 2011. Research Methods in Education. 7th red. Abingdon: Routledge.

Creswell, J. W., 2003. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 2nd red. California: Sage Publications.

Denscombe, M., 2014. The Good Research Guide for Small-Scale Research Projects. 5 ed. Berkshire: Open University Press.

Dowling, M., 2004. Hermeneutics: an Exploration. Nurse Researcher, 11(4), pp. 30-39.

Feilzer, M. Y., 2010. Doing Mixed Methods Research Pragmatically: Implications for the Rediscovery of Pragmatism as a Research Paradigm. Journal of Mixed Method Research, pp. 6-16.

Guba, E. G. & Lincoln, Y. S., 1994. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. i: N. K.

Kakkori, L., 2009. Hermeneutics and Phenomenology Problems When Applying Hermeneutic Phenomenological Method in Educational Qualitative Research. Paideusis, 18(2), pp. 19-27.

Laverty, S. M., 2003. Hermeneutic Phenomenology and Phenomenology: a comparison of historical and methodlogical considerations. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2(3), pp. 21-35.

Mackenzie, N. & Knipe, S., 2006. Research dilemmas: Paradigms, methods and methodology. Issues In Educational Research, pp. 1-11.

Merriam, S. B. &. T. E. J., 2016. Qualitative Research – A Guide to Design and Implementation. 4 ed. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Mertler, C. A., 2016. Introduction to Educational Research. 1 ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Morgan, D. L., 2007. Paradigms lost and pragmatism regained: Methodological implications of combining qualitative and quantitative methods. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), pp. 48-76.

Morgan, D. L., 2014. Pragmatism as a Paradigm for Social Research. Qualitative Enquiry, pp. 1045-1053.

Paterson, M. H. J., 2005. Using Hermeneutics as a Qualitative Research Approach in Professional Practice. The Qualitative Report, 10(2), pp. 339-37.

Senaste kommentarer